In Conversation: Interview with Doctor José Antonio Bastos, President, Médicos Sin Fronteras — España

Name: José Antonio Bastos

Born: Jaca, near the Pyrenees, Spain, 1961.

Lives in: Madrid.

Profession: President, Médicos Sin Fronteras (Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders) — Spain

Work: GP, Red Cross, MSF.

Education: University of Madrid, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

Favourite book: Empresas y Tribulaciones de Maqroll el Gaviero by Alvaro Mutis.

Last film watched: Where Do We Go Now? by Nadine Labaki.

Media: Al-Jazeera English, BBC World.

-

José Antonio Bastos is the President of the Spanish branch of Médicos Sin Fronteras España (Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders), a humanitarian-aid NGO famous for its vital work in developing countries and war-torn regions. An engaging, principled man, Dr. Bastos first joined MSF in 1991, while working as a GP in Spain. After missions in locations such as Bolivia, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Somalia, he worked in Iraq and Afghanistan for the Red Cross. In 2010, he was elected president of Médicos Sin Fronteras Spain. This year marked the 42nd anniversary of MSF’s founding, but as Dr. Bastos reveals, the NGO still faces a constant struggle to help those in need.

– – –

I wanted to start quickly by talking about you. Is your first time in Argentina?

Second. I was (here) early 2011. Part it is my role as the president is to help on the streamlining of the principles, the ideas, the enthusiasm, to look at the challenges. In Latin America, and specifically in Argentina, we have been for nearly 12 years now recruiting health professionals and it has gone way over (the) expected results. We have, we have more than 100 health professionals, extremely well qualified, who have proved to be very loyal and have stayed (with us). It’s a very important community…

And you have a major office in Brazil?

We have a big office in Brazil. We have five, the five, operational hubs across the MSF movement, are historically, they are Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam, Barcelona and Geneva. All the other 20 offices in the world, they are fundraising and recruitment, like in Argentina. There is one in Brazil, following up Brazil and around, one in Mexico, which follows up Mexico and central America, and one in Buenos Aires that follows up all the rest of Latin America, cono sur, a bit of, from Colombia to southern Chile, that’s all from Buenos Aires.

And in terms of major operations going on in Latin America now, do you have anywhere…

There’s no major operations in Latin America. And that’s good news for Latin America. (Laughs.)

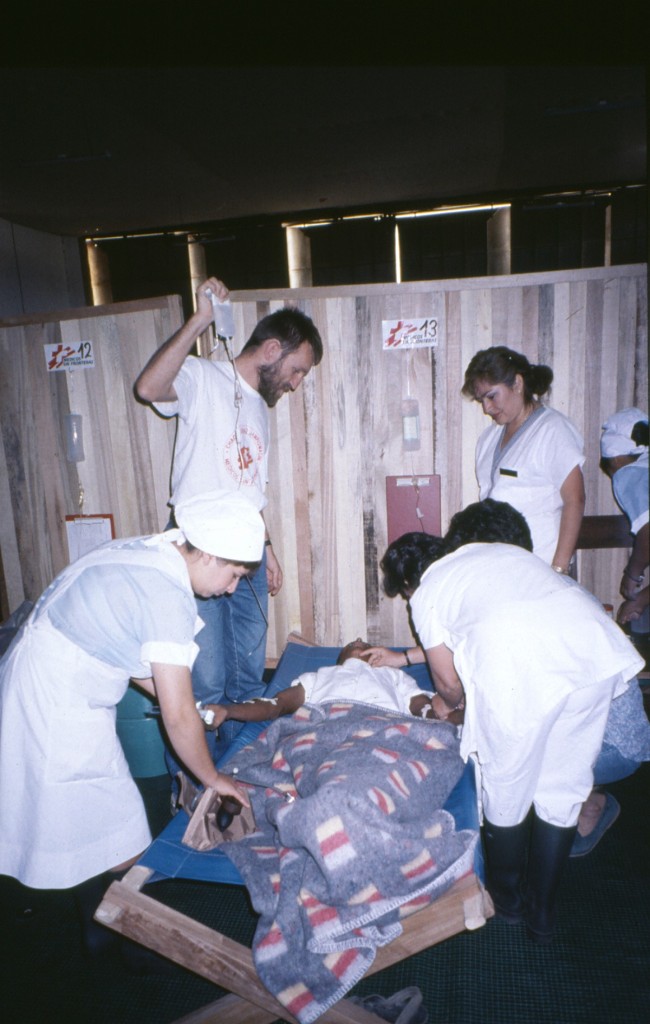

Dr. José Antonio Bastos (bottom left), poses with fellow MSF workers, during the training of health personnel during a cholera epidemic in Cochabamba, Bolivia, in 1992. © MSF

Well, we had a report yesterday that’s said there’s still 47 million people below the hunger line in Latin America. There are still things that can be done here, I would think.

Certainly, but it depends how dramatically and how many other actors are there to do it. I don’t think Latin America is on that end of the famine situations we have seen in Somalia, that we see year after year in Niger, that we see in some parts of Ethiopia. It’s not the same level.

I think here, there are ministries of health that are more or less committed, more or less capable and in the other places we work, we have failed states… and that, that’s a dramatic difference. So, we have been called very often here in Argentina and by those in Spain with the crisis, ‘Why don’t you do something here?’ And once we try to, or we start assessing how to do something in these parts of the world, we find there are so many actors already doing interesting things.

You worked with MSF in Bolivia when you were younger though. Is that some kind of historical change? Were there more operations here in the past?

There’s some historical change, in a sense that… I think there was a time in MSF Spain when we really were trying to do, we found it wasn’t possible, both development and humanitarian work, a bit like other NGOs do a little bit. We have been in Argentina, I think in 2001 to assess the situation, and we did a short intervention in the availability of medicines to the population, it was not to provide healthcare but to streamline access to medicines to be available. But these are exceptions.

“I don’t think Latin America is on that end of the famine situations we have seen in Somalia, that we see year after year in Niger, that we see in some parts of Ethiopia. It’s not the same level.”

Dr. José Antonio Bastos, pictured working for MSF during a cholera epidemic in Cochabamba, Bolivia, in 1992. © MSF

What was Bolivia like then?

Oh, fantastic! Poor, poor, part of the world, undeveloped country, where (the) poverty struck me… but so, so… it might sound cheesy, but the people were really, really, sweet. I heard now that Bolivia has gone a bit more… in Cochabamba, in ‘92, that was really really nice to interact, they interacted with our colleagues, our primary healthcare doctors, it was fantastic, I’ve never had it again. The population really thankful, I dunno, it was a very special feeling.

One thing I was interested in, I understand that there’s quite a high dropout (with doctors) after the first mission.

Yes, there’s a high level of drop-out… but it’s not a high level of drop-out on a full-life contract. It’s that, structurally, we invite people to join us just to do a one-year experience in their lives. There is a level of efficiency. They want to work two weeks with us, it would not work… but if you want to do a year, two years of your live, that’s within the system, we count on this and that’s what we want.

I notice with a lot of your organisation’s communications was a tendency to push the people on the front line to the front, so to speak.

In our case it’s not a technique. I think, in general terms, y’know that MSF has this dual aspiration in the world from its creation. It was created by a bunch of doctors and journalists from a medical magazine and this is one of the reasons why we play it up, it’s because we believe what should be seen, should be told. A very active role of témoigner in French, ‘witnessing’ in English.

We don’t like to sweeten things too much and often we have felt, understandably, and with the whole issue of the ‘pornography’ of misery… we pride ourselves on saying whatever situation we find ourselves in. We don’t make a big marketing assessment about what we expose to the public, we try to tell things as they are. We’re not very marketing/image obsessed and you see maybe a little more with the political intention rather than the marketing intention.

Aren’t there two facets to it? Your message to recruit doctors is a different message that you want to give out for fundraising, no?

No, we use the same message. We don’t nuance that. It’s a little bit French arrogance… (Laughs) No really, it’s a little bit of French arrogance, and honesty in saying ‘This is what we are. If you don’t like us, or find us, go to the next to the right, or the next to the left, another NGO, whichever one you want.’ It’s honest.

I’ve never heard that being said (at MSF), different message for fundraising, different message for recruitment. We project an image of what we are for the fundraising, for the communications at large, that is used for fundraising, recruitment and for political impact — all three together. So MSF as a whole, has an air of slight arrogance in that, ‘It’s ok if you don’t like me,’ ‘if you don’t like me, piss off…’

For MSF Spain in particular, I remember in ‘95, I was in headquarters, I remember perfectly, a crucial moment where, a very successful guy, the new director of communications and fundraising together, he proposed two clear strategic options, he said: ‘We can start going aggressively for fundraising, with fundraising triggering messages and image, or we can try to go much farther with a bit more of an activist approach to try and capture not only the pocket but the heart and the mind of a big chunk of the Spanish society to support us financially, politically if necessary, and make them feel like they’re really supporting us. This will give us a much slower increase in the number of people supporting us but much more loyalty.’

At that time there was a short discussion, the majority of people didn’t want the short-term message, and they were really attracted to the ethical part of the long-term idea. We want to be honest. The people who are supporting us should be doing it because they believe in what we do. The proof, the decision, can be seen as we’re gone through the crisis in Spain, with a slight drop-out in the average donation, with nearly no drop-out in the number of people who join us and with the same rate of increase, 10 percent, every year the number of people who join us, which is shocking.

“We don’t make a big marketing assessment about what we expose to the public, we try to tell things as they are.”

There’s one thing related to that that I was looking at yesterday, which was about this book of yours (the organisation), Humanitarian Negotiations Revealed (a book published ahead of the organisation’s 40th anniversary, which exposed the often uncomfortable compromises international aid NGOs are forced to make while working in conflict zones). It draws me into some of the bigger operations today too. One that’s very interesting for us is Syria and I wondered what engagement you had… I know you’re in rebel areas…

Do you know why?

“MSF as a whole, has an air of slight arrogance in that, ‘It’s OK if you don’t like me, if you don’t like me, piss off.'”

As I understand it, correct me if I’m wrong, because they will let you into those areas and the government (of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad) won’t allow you into their territory.

Very very bluntly: we have been for two years investing big efforts to be allowed to work on the government side and we’re still not allowed. And we have invested big efforts in working in extremely complex guerrilla areas and we have managed, with limited success. It’s not that we are (doing) as much as we wanted or all we wanted, but we have a much bigger difficulty in getting to work on the government side, which happened exactly the same in Libya. Exactly the same, which raised a wave of accusations among the leftists in Spain and around the world that we were supporting NATO strikes… that’s linking a bit to the bigger picture.

Humanitarian, no, any type of aid in history has always been manipulated by political powers, there’s no doubt. Humanitarian aid, in particular, has been very thoroughly used in the military part of the world on terror. I was in Afghanistan for nearly two years and I saw it firsthand and it was shocking the degree to which militants, driving in white cars, in civilian clothes, pretending to be a NGO… this has raised an extreme identification of humanitarian work with Western military offensives in these countries and it’s gained us an amount of distrust and blockage for access that I think is hurting us now in Syria, and we paid in Libya. It’s just governments who are not aligned with the Western powers, they just distrust humanitarians as a whole, because they have seen, like in Afghanistan, how they (the groups) have been used in other parts of the world.

Some governments have done that too haven’t they? I remember the furore at the time about the (Osama) bin Laden operation in Pakistan for example, they used a vaccination programme…

That’s atrocious. I’m glad you bring that up. It was not as cover, it was to get genetic material to identify him but that’s atrocious and not everyone knows it. I mean, I’m glad you’ve heard about it, although that’s a bit of an extreme example…

But you can imagine the impact, you see the image in this case was more purely medical, but by using this, how many, how many, specifically, vaccination teams for polio have been killed since then in Nigeria, in Pakistan… lots. How many children in the world have not been able to be vaccinated in the last five years because of it?

Whoever made that decision in the CIA, or in the Pentagon, I don’t know whether they were putting it in the balance as to whether they should, but they should’ve known the impact it would have on millions of people. They were burning down that tool, that possibility, and they were extracting from a significant part of the human population that receives aid, or medical assistance, by using it as a tool for their own maybe-justified political ambition, but that’s where the importance of neutrality comes into place. I think they are things that should not be used to hit each other because they have to be preserved.

“We do it to support people and in the process of assisting people we come across huge political failures, but our point of departure is not a political choice.”

But aren’t there times that MSF takes a stance as well? I know obviously, it’s a very sensitive issue to the organisation, but I would think of (MSF pulling out of) Somalia, for example, purely by pulling out, that’s a political decision in itself isn’t it? The organisation is still taking a stance..

You’re talking about the unavoidable… what do you think about the fact that we felt we had to communicate about the toxic agents in Syria?

You see, one thing is the unavoidable political consequences of any political action — some actions have big political consequences. I have worked in South Sudan, with lots of other organisations on the ground who were radical Christian American organisations who were there to support their fellow Christians. The reason they were doing it was for their religious, political affiliation and preference.

In Spain, the pro-Palestinian cause or the pro-Sahara cause, people are very very rooted in some sectors of society, there are some people who do not understand that we’re in Palestine to assist human beings who are having a tough time, independent of who they are. We don’t do what we do in general or in any specific context out of political preference or sympathy. We do it to support people and in the process of assisting people we come across huge political failures, but our point of departure is not a political choice. Which is different from the political consequences of what we say or do. I don’t think we are very political.

Would the proposed Geneva 2 peace negotiations help MSF?

It would be helpful for the Syrian population first. And hopefully, it would go far beyond the humanitarian access. It would be really helpful, yes, if they brought in humanitarian access… there’s quite a few enclaves in Syria now where starvation is becoming an issue and lack of medicines etc. When the international community looked at chemical weapons as a serious issue, they gained access to these enclaves. So access is possible, if it’s negotiated politically correctly. We do not have access to bring in food… it’s absurd! That’s one of the things we’ve been asking for. If you have managed to get the access for the chemical weapons technicians, why can’t we go in with a few trucks of food? That’s absurd.

MSF is not a political organisation, but we would love to see peace negotiations in Syria moving on. We are horrified and we are first-line witnesses of this civil war and someone, somewhere has to stop it. We cannot. We are not a political negotiating organisation but we’re really worried that this is going far beyond any other civil wars or conflicts we have been in.

We are running seven hospital with around 100 local workers from cleaners, maintenance, to surgeons, you need people to cook… and then we have a network with logistics and some health professionals in between — international and MSF — to support the existing structures, we go, we assess them, to help them and supply them. We are always very, very paranoid and suspicious of what happens all around the world with the use of the supplies we give.

We feel quite overwhelmed, honestly. We do our best but we think many other international organizations should step up and come in. We have called many times for organizations to enter and negotiate with the countries around, and with the government, to be a bit more pushy. The population on the rebel side has enormous needs.

What about the Philippines? One of the stories we kept hearing was that nobody could get to Tacloban. Doctors were stuck on runways for days…

Well, in natural disasters it’s different. That happens. In natural disasters, local armies are very, very helpful in providing support to everyone. In natural disasters, it’s different, there is not the high political sensitivity like we have in Syria.

It was just impossible to find boats, to get planes. For us, we are used to working in different cultures and disaster response, but it’s been shocking how difficult it was in the Philippines. On the contrary, as it’s nice to not only give bad news, we had civilians come out of the crowd to help offload cargo from our planes. ‘Can I help you?’ That hasn’t happened to us before and it’s very much appreciated. It gives you a very different feeling.

Tell me about a project that doesn’t get any press or one that you think needs more fundraising or publicity.

The Central African Republic. That’s probably the best example, yes. I was talking at Chatham House (Home of the Royal Institute of International Affairs, in London) last Friday, it went very well, I think we managed to shake the British government on that… it’s a battle…

From an operational point of view, one of our criteria to prioritize international interventions is, is it what we call a ‘forgotten crisis’? Is it a place where… it’s not just the funding, the communications, the press is not interested, there’s no funding, there isn’t a political interest in it.

Central African Republic has been, certainly for the last two years, probably the one that gets little, Somalia was for a long time, until the famine in 2008, when it was completely forgotten, we were making big efforts to remind the world that that was an enormous refugee camp, so for us it’s a constant crusade, or… endeavour — that’s the English word — to keep taking out of the dark these horrible situations in the world.

And can you operate with the acting leader now, Michel Djotodia? Will he engage with you?

Yeah, oh yeah. He’s a well-known contact of ours. When he was in charge of one of the rebel groups in the North, we were working in this area, and already had contact with him.

He’s one of the leaders of a cluster of rebel groups… it’s very much widespread banditry, the rebel groups. But Central African Republic is very difficult to work (in), and the UN has withdrawn, after the last event, after the coup d’etat… I mean, they were behaving in Central African Republic as if it was Iraq. Come on, it’s dangerous but it’s not the same. The country is unstable, mostly with looting and banditry, and since September, with the new wave of violence by religious groups, targeting civilians, but we have managed to reactivate our programmes and to scale up to four additional projects. But why can we do it and not the UN? Why cannot other international organizations do it? They should.

A majority of humanitarian and medical interventions in the world are in Africa. It’s not a purposeful choice, it’s a reflection of how the world is today.

From an operational point of view, one of our criteria to prioritize international interventions is, is it what we call a ‘forgotten crisis’?

You have to make a choice when you go into an area as to whether something’s possible? Because sometimes it can’t be worth it.

That’s why we withdrew from Somalia. It was not possible to work there.

Wasn’t that security?

Yeah, but that’s one of the reasons why you can’t operate. There’s a few other situations where we can’t operate. In North Korea, purely because of sheer government control and manipulation to the limit where we have to withdraw. We can’t operate in Iraq out of security. We withdrew from Afghanistan for nearly five years. Normally the reason is security.

I should talk to you about Somalia and the kidnapping. (MSF workers Montserrat Serra and Blanca Thiebaut were abducted from the Dadaab refugee camp, Kenya, on 13 October 2011. They were later freed after 644 days in captivity.) What do you do in a situation when someone’s been kidnapped and you have no information about them. Do you have to lobby the national governments?

We do every, every, everything we can. And that includes lobbying, speaking to our contacts, that’s anywhere in the world. It’s an issue, I prefer not to give too many details for the implications on other people kidnapped in Somalia… but in general, our response is to try and activate all the networks of contacts we have, as far as possible, to see if there is any lead that can help us to get them out securely.

I have to tell you, the support we have had, the cooperation of the Spanish media and the international media… at this point now, the discretion of the press,it’s really helping the girls a lot with their lives.

“It’s shocking that in today’s world, health is a business, not to the point where some people make a profit on it, but to the point that people who do not have enough financial capacity, (they) are not an interesting market and hence, their diseases are not researched.”

Another thing I wanted to talk about quickly was about drugs and international property rights. I wondered if there’s anything you’d like to say about that?

Well, that’s a long one… (laughs) from the broader picture to the detail, it’s shocking that in today’s world, health is a business, not to the point where some people make a profit on it, but to the point that people who do not have enough financial capacity, are not an interesting market and hence, their diseases are not researched, are not funded, neglected diseases that affect selectively poor and destitute people like the Chagas disease in Latin America, Sleeping Sickness in Africa… there hasn’t been any progress in research and diagnosis since the ‘30s or the ‘40s.

The treatment for Sleeping Sickness is arsenic salts toxified so they kill the parasite before they kill the person… it’s brutal, it’s a level of primitiveness that you wonder – and the only reason why it hasn’t moved on – compare this to Viagra – the only reason was because the people who suffer disease have no money, and really, it looks like natural selection. I mean, they don’t exist for the world. And that’s something we have really stood up against.

When we were getting our teeth into the AIDS pandemic in the mid-90s, when we decided to jump into it. We found really that the main reason, the reason the virus came into place, the main reason why millions of people in Africa were suffering from this was just the price was too expensive. And then we did our little homework of finding the cost of the raw materials, the cost of production, we found the companies were making an absolutely unacceptable level of profit. And then we started cornering them and pushing them to release or to allow generics and that’s…

I don’t know if you know the very famous quote but it’s something like the price of one anti-viral treatment for an average African in 1998 or 1999, before we managed to push for the generics was around a US$1,200. After the generics came into (their) place, it dropped to US$100. And with US$100 the laboratory still made some little profit. So there is, I think in today’s world, as it is organised – you could dream of a different world.

The promotion and use and distribution of generics is the solution to that problem. And that clashes with the patent laws, for example, and that has to be… not only ironed out – we have won a few battles and we have fought them but I think it needs to be permanently monitored because it’s involves constant counter attacks from the (pharmaceutical) industry…

Changing the subject, have you had donations drop in Spain, out of interest?

We have the number of donors had stayed really high, as I said, all through the crisis, but the average donation has decreased. People are staying, but they are decreasing the amount they contribute. With personal records, I do a round of face-to-faces with people who are doing the recruitment of supporters and the phone… what do you call it? The phone answering… the call centres! I meet people at the call centres regularly, once a year or so, and the last time I visited the call centre, they always tell me stories of the dramatic calls, I listen to a couple of them and people call saying ‘I lost my job, I have three children to feed, I’m really sorry…’ Some people even crying, ‘I have to decrease my funding or my contribution.’

It’s really… I’m very impressed how personally committed our – I think we have really succeeded in making our supporters feel personally committed to MSF.

You have quite a good amount of brand loyalty…

If that’s the name you give it…

I was interested… are there projects running in Spain at the moment?

No.

“People have to have healthcare when they need it.”

Do you take a lot of flak for that? Do people not say ‘Oh, what about all these people at home?’

We are often asked about it, and as you said about Latin America, luckily, Spain doesn’t need MSF. It’s not good, there are lots of NGOs, particularly MDM and Red Cross who are present and have expertise that we do not have in working in the social environment in Spain, so while there’s not any need for us, why should we be competing?

A question that I think’s much more sharp and much more intelligent is why, with what is considered our big mouth and our voice, why we have not been taking a much more stronger, public position on issues like the withdrawal of the healthcare from the migrants in Spain. That’s a much more difficult question. Because there, I think we could be a bit more active. Like there to make a public statement, politically. A public statement saying, ‘All human beings have the right to receive healthcare when they need it.’ You could express it like this.

Certainly, illegal migrants in Spain and everyone knows they should receive the medical care they need. Anywhere in the world, irrespective of whether it’s MSF who gives it or not. And if something like this happens because a government chooses to withdraw it, we don’t like it. People have to have healthcare when they need it.

One more thing. I just wanted to ask why you originally started working for MSF. What was your motivation?

My motivation, I think first, is very, very linked to my motivation to decide to be a doctor. It’s a bit of a mix of curiosity for human beings and an intense drive to help other people when they’re in need. But then, when I was a doctor, I realised I wanted to do something special with it, I didn’t want to be just another doctor, doing the normal doctor boring normal work, and I thought ‘Normal medicine or Africa?,’ tropical medicine, and then as I was growing through my youth and my medical studies, there was a combination of the TV news, and I remember very well the civil war in Lebanon, which really revolted me from the TV and I remember thinking, ‘I would like to do something… to be doctor, to go there.’ It was very, very instinctive.

And then I had the luck that I did my medical studies, I did my practice studies in the Red Cross Hospital in Madrid, that was taking care of the medical needs of the very, very sick, more refugee community that there was there at the times and then I came across Iranians, Iraqis, that told me about the wars in their countries and I thought, well…

A little hands-on experience?

That’s what I wanted to do. And then I did a search when I was finishing my medical studies, I rounded up all the available volunteers for charity options in Spain — half of them Catholic missionary, half of them strongly-Leftist political movements and then I came upon MSF, which was much more expressing what I wanted: a pure, instinctive, humanist drive to assist other people.

And I thought, ‘What is wrong with them?’ And then on my first mission, I was…

You were sold?

Instant romance. I thought, ‘This is what I like.’

Is that the most important ingredient for someone that wants to work for MSF?

What?

Passion.

I think you cannot do MSF without passion.

An abridged, edited version of this full-length interview was published in the Buenos Aires Herald, on Sunday, December 22, 2013.

Link: http://www.buenosairesherald.com/article/148035/we-believe-what-should-be-seen-should-be-told.

© J. GRAINGER, 2013